Sir Charles Rowan and the Origins of Modern Policing

Everyone with a basic knowledge of the history of policing in the western world will know the name Sir Robert Peel. Far fewer, however, will know the name Sir Charles Rowan. Peel was the UK Home Secretary, who in 1829 introduced and shepherded through parliament the Metropolitan Police Act, which brought the London Metropolitan Police into existence. The agency would serve as a model for police organizations throughout England, the rest of the commonwealth, and the United States. Previously, Peel had introduced several significant reforms to the criminal law, including the repeal and consolidation of numerous statutes that had become redundant and confusing over the previous years. It is the name of Robert Peel from which the nickname for Met officers, “Bobbies” was derived.

Sir Robert Peel

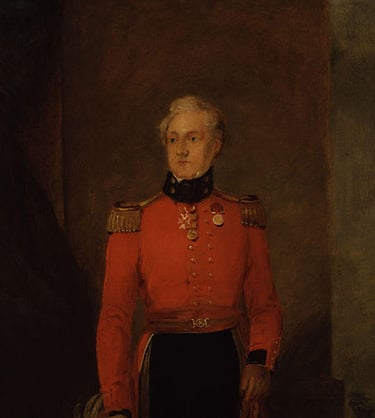

While Robert Peel is remembered by history as the father of British Policing, it was Sir Charles Rowan who, along with Sir Richard Mayne, led the Metropolitan Police as the first commissioners in the critical first years after their founding. Like the Prime Minister, Arthur Wellesley, The Duke of Wellington, Sir Charles Rowan was a former British Army officer and veteran of the Napoleonic Wars. During his time in the army, Sir Charles served in the 52nd Regiment of Foot under the unit’s commander, Sir John Moore. It is to this unit and its officers that the British police, and policing in the western world, may owe more than a bit of its character.

In 1803, the 52nd Regiment became the first regiment in the British Army to be designated a Light Infantry regiment. In general, when thinking late 18th and early 19th century warfare, the image brought to mind is of massed infantry, armed with muskets, and formed in close-order formations, confronting an adversary roughly formed in a similar, shoulder-to-shoulder formation. This is Line Infantry. In contrast, light infantry were deployed in open-order, acting as skirmishers in small units to harass and disrupt enemy formations, counter their skirmishers, or protect the flanks of large formations. While most European armies had deployed such troops to a lesser or greater extent, the British did not fully embrace them until the outset of the 19th century.

Among the distinctions that set light infantry apart from the more traditional line infantry, was an emphasis on individual skill and initiative. The 52nd received its light infantry training at Shorncliffe Redoubt, a British Army camp on the south coast of England. The training was unique for its time, in that the officers performed battle-drills with their men. This was unusual at a time when very few officers received any formal military training, much less perform drill in the field with the enlisted personnel. The training received by the soldiers at Shorncliffe was developed by Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Mackenzie with an emphasis, not only on perfecting the basic skills required to effectively employ the infantry arms of the day, but how to act on initiative, to think independently, to adapt to changing conditions and to take an active role in the battle.

Sir Charles Rowan

Along with the efforts of Lieutenant Colonel Mackenzie in revolutionizing the training of the unit, Colonel Sir John Moore made equally revolutionary contributions to the general philosophy that characterized leadership and discipline in the 52nd. During his time at the head of the British Army of the day, the Duke of Wellington was quoted as saying, “We have in the service the scum of the earth as common soldiers.” However there are a number of accounts left by veterans of the 52nd describing their admiration for the officers who led them and for the lessons learned of leadership while serving in the unit, which suggest that officers of the 52nd took a far more flattering and enlightened view of their men.

General Sir John Moore

A later writer, Lieutenant Colonel W. Clark noted that Moore’s system of leadership and discipline was based on the following principles:

That it was necessary to have the officers efficient before the men, and to require of the officers real knowledge, good temper, and kind treatment of the men.

That power should be delegated to officers commanding companies; the men to be taught to look up to them in matters alike of drill, food, clothing, rewards and most punishments.

That all officers and non-commissioned officers were to understand that it was their business to prevent rather than punish crime.

In an age where much of military discipline consisted of a liberal application of the lash, this approach was revolutionary indeed. What may have been a novel experiment, carried out by another eccentric officer may have never had much influence, except for one key factor. It worked. The 52nd was singled out for praise of its discipline and efficiency by contemporary and later observers alike.

It was under the reform minded leadership of Colonel Moore and Lieutenant Colonel Mackenzie that Charles Rowan spent his service with the 52nd, later to be chosen for a post where he would have an incalculable influence on the development of professional policing in Great Britain and throughout the western world.

That influence would take the form of both practical as well as philosophical aspects of organizing the police. From the organization of officers into divisions, sections and beats, to the relationship between officers and their superiors, and even the emphasis on prevention, rather than punishment of crime; much of the character of the early London Metropolitan Police could be traced to the pioneering work of Colonel Sir John Moore, Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Mackenzie and the primary force for shaping the early British Police, Sir Charles Rowan.

Living as we often are, in an age of reform, it can be easy to focus on new ideas, new technology, new solutions and discount any lessons that may be learned from the past. The problem that is unaddressed however, is that the foundational principles of policing under English Common Law remain as sound as they were when the Metropolitan Police first took to their beats in 1829. It is in straying from those basic, foundational principles that we often find ourselves in need of reform. Having attempted to fix various mechanical contrivances that I didn’t understand, I can say with confidence that understanding the nature of something, how it’s designed and on what principles it operates, is critical to successfully addressing a problem.

If we are to be true leaders in any field, we owe it to ourselves and to our professions to be students of our craft, aware of not only where we are, but where we started.

M. T. Rush